The Lowdown on How to Protect Property Against High Water in the Great Lakes

Water in three of the Great Lakes (Erie, Ontario, and Superior) reached its highest level in a century in 2019, and more of the same is forecast for 2020. Public agencies, consultants, and homeowners are scrambling to react, and emergency permitting has been offered by at least one state’s environmental protection unit to streamline preparations for 2020. The Great Lakes encompass 14,000 miles of shoreline.

About the Expert:

Craig Schuh, PE, has 22 years of experience and is responsible for managing and designing municipal and site civil projects. He manages Ayres’ municipal engineering group in Green Bay, Wisconsin.

While Lake Michigan and Lake Huron did not hit records last year, they did come within 1 inch of setting a monthly record in December, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers forecasts that these lakes will exceed their highest monthly recorded levels (in 100 years of recordkeeping) in February, March, April, May, and June of this year.

When the ingredients of storm surge and high waves are added to those historically high water levels, it’s a recipe for property loss and risks to homes, docks, and other structures. Among the many manifestations of these conditions was a January storm that caused millions of dollars of damage up and down the Lake Michigan coast from Milwaukee to Chicago.

The Great Lakes’ water levels rise and fall in accordance with two different cycles. One is the annual fluctuation that brings water levels somewhat lower each winter and somewhat higher each summer. The other cycle is an overall tendency for the lake levels to dip and then rise approximately once per decade based largely on the ebb and flow of precipitation and runoff in the basins that drain to the lakes. In fact, an especially long low-water period that began around 1999 lasted until 2013, when Lake Michigan and Lake Huron were near 100-year lows. Rising rapidly ever since, those lakes now are poised to set monthly records through June.

Setting the Stage for 2020 Threat

In the Great Lakes region, 2019 was the wettest year on record in the past 120 years, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. December 31, 2019, also marked the end point of the wettest two-year, four-year, and five-year precipitation periods for the overall Great Lakes Basin. NOAA projections for January through March 2020 show wetter than normal weather for the Great Lakes.

On the minds of many Great Lakes communities and residents is the question of how to protect homes and public infrastructure against the erosive effects of the high water’s constantly lapping waves and the periodic push of storm-driven surges and crashing waves.

Tools to Fight Against High Water

A number of tools are available to those looking for solutions:

- Lidar data collected from the air to identify the location and elevation of local infrastructure can be combined with projected lake levels to give communities flood mapping that shows likely areas of inundation and assesses what infrastructure is threatened. Storm surge and seiche of 1 or 2 feet is common and also taken into account in such mapping.

- The next step is to help communities move forward with a plan that prioritizes possible projects aimed at mitigating erosion and improving resiliency. With assistance, communities can prioritize projects and plan for funding based on accurate cost estimates.

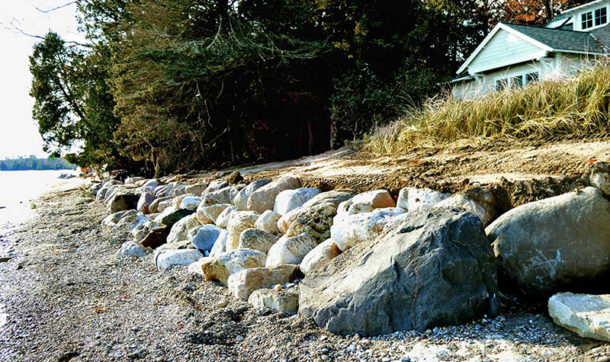

- Solutions can include erecting seawalls or riprap to combat erosive wave action. Valuable assets such as roads and parking lots can be raised or moved to get them out of harm’s way.

- Coastal landowners who are literally losing ground to the Great Lakes can take action to protect their property with riprap and other revetment options if their situation involves the undercutting of the bluff or other high ground upon which their home is built.

An Emergency Option to Speed Permitting

In at least one state, true coastline emergencies now can be dealt with rapidly with an emergency permit. The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR) in December unveiled an emergency permitting option that allows property owners to self-certify their planned revetment work by completing a one-page permit. They can then go ahead and install riprap while pursuing the usual 120-day individual permit process to receive a regular permit for the work. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and County zoning departments also need to be consulted about permitting, which are contingent on site and project characteristics.

In at least one state, true coastline emergencies now can be dealt with rapidly with an emergency permit. The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR) in December unveiled an emergency permitting option that allows property owners to self-certify their planned revetment work by completing a one-page permit. They can then go ahead and install riprap while pursuing the usual 120-day individual permit process to receive a regular permit for the work. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and County zoning departments also need to be consulted about permitting, which are contingent on site and project characteristics.

The emergency permit does not excuse the homeowner from adhering to all the regulations that govern the regular permit, and if the work is done improperly, the project has to be removed or corrected. The emergency permit is primarily aimed at riprap projects, and here’s a summary of some of the WDNR requirements the permit lists:

- Riprap material must be large and angular enough to resist waves’ ability to pull it into the lake.

- Filter fabric must be used under the materials. This resists soil loss under the riprap, which undermines the revetment.

- Materials must be placed at a 2-foot-horizontal-to 1-foot-vertical maximum slope.

- Material must be placed along the natural contour of the shoreline.

Keys to Designing Riprap That Lasts

Riprap projects can be costly, and spending a lot of money on a lot of rock can be a waste of both since rocks that are not massive enough (hundreds of pounds or even tons per rock) or angular enough will inevitably be dislodged and pulled into the lake under harsh storm conditions. And the slope needs to be correct for the riprap to properly dissipate the force of the waves as they hit; the steeper the slope, the larger the rock needs to be. Other design features that may figure into a project’s effectiveness include:

- Especially massive rocks partially buried at the toe of the riprap revetment will best anchor the riprap.

- A splash apron of smaller stone above the wave line will prevent spray from the crashing waves from cutting away soil above and behind the main armor stones of the riprap.

- Properly installed geotextile fabric minimizes movement of sediment and reduces the effects of groundwater coming out of the bluff.

- Neighbors who cooperate in installing revetment uniformly across several properties will get better results than a piecemeal approach where revetment just deflects wave force onto adjacent unprotected shoreline.

Additional Anti-erosion Designs

Other means of battling erosive forces along a coast include:

Seawall: The disadvantage of building a vertical seawall is that it does not dissipate the force of the waves that crash against it. Seawalls also impede some animals from moving between the water and shore. Municipalities that want to maintain the ability of boats to navigate directly up to a shore may choose seawalls rather than sloped riprap. Although common, permitting of new seawalls is particularly challenging and may not be an option.

Breakwater: Constructed as linear features (often riprap) offshore and parallel to the shore, a breakwater dissipates wave action before reaching a beach or bank.

Groin: A feature that juts out perpendicularly to the shore, a groin serves as a way to increase the deposit of material on a beach or bank on one side of the groin by creating a protected area for particles to settle.

Reach out to Craig Schuh, PE, to learn more about the impact and remediation of high water in the Great Lakes. And check out our River Engineering + Water Resources division and Geospatial division service pages to see some of our strategies in action.

Post a comment: